Science & Environment

Science & Environment

The brutal killing of a Detroit man in 1982…

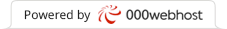

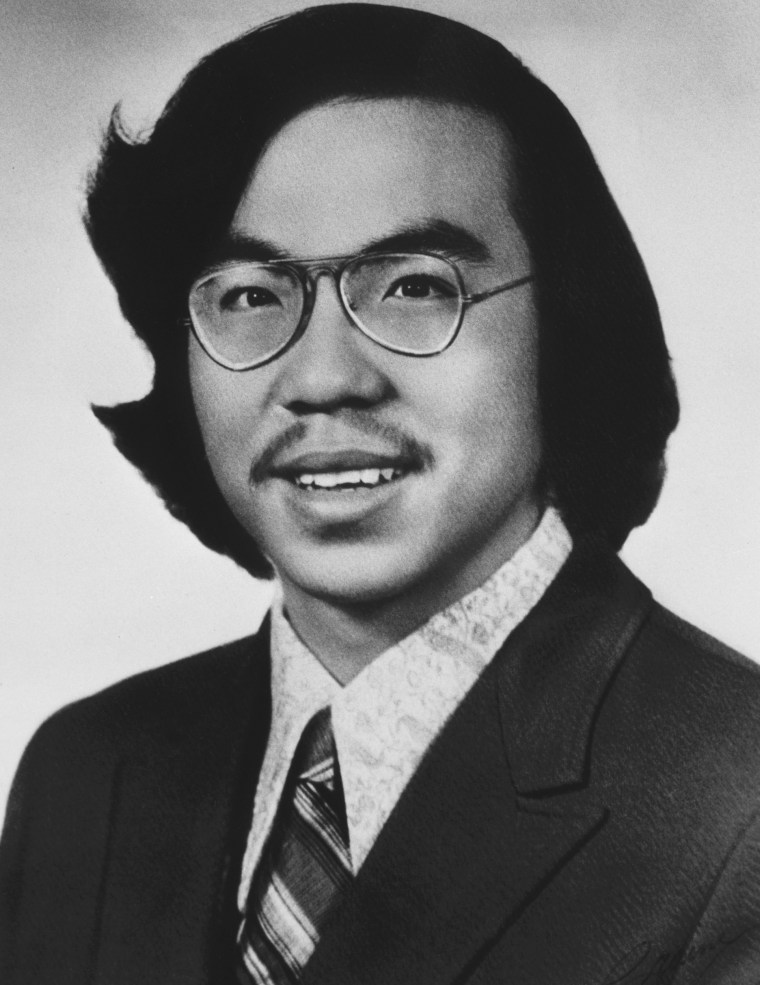

Two white autoworkers bludgeoned 27-year-old Chinese American Vincent Chin to death with a baseball bat during his bachelor party in Detroit in 1982, but his loved ones’ cries for justice fell on deaf ears.

Twelve days passed before any media outlets reported Chin’s killing by men who blamed Asian manufacturers for the downfall of the city’s mainstay auto industry, and none acknowledged the racism in his killing at the time. The defendants pleaded guilty to manslaughter and were sentenced to three years’ probation. Circuit Judge Charles Kaufman reasoned, “These aren’t the kind of men you send to jail.”

The injustice spurred Asian Americans to unite across ethnic and cultural lines. Hundreds protested the trial’s outcome in downtown Detroit. Chin’s mother traveled the country sharing his story and pushing for a federal civil rights prosecution.

More than four decades later, activists still fight to ensure Chin is not forgotten, saying his story inspires advocacy nationwide. Law students reenact his trial, Hollywood adapted his story into a movie and Asian Americans remember the impact of his killing on their struggle for racial justice and equality.

“For a whole generation of Asian American activists, the Vincent Chin case was the case that got them involved,” says writer and filmmaker Curtis Chin. “It was the thing that brought them to the table.”

A chorus of Asian American voices

After the judge spared Vincent Chin’s killers, Curtis Chin — then 14 — grabbed his parents’ typewriter and wrote outraged letters to newspaper editors. He had found his calling.

Instead of taking over his family’s Chinese restaurant, Curtis Chin — who is not related to the man killed on June 23, 1982 — spent the next 30 years elevating Asian American voices, and recounting Vincent Chin’s story and the racism of 1980s Detroit.

For Helen Zia, an Asian American activist who moved to Detroit in the 1970s, Chin’s case laid bare the glaring injustices that her community faced.

Lacking any local organizations to advocate for Asian American civil rights, Zia co-founded the American Citizens for Justice, which helped to secure a federal trial against Chin’s killers. One was acquitted of civil rights violations and the other was convicted and sentenced to 25 years in prison. His conviction was overturned on appeal.

On June 20, the FBI released a 602-page file on Chin’s death, revealing previously unseen witness interviews with descriptions of his final moments and the anti-Asian slurs his attackers used, among other details. Activists told the Detroit Free Press, which first reported on the FBI documents, that they were not notified about the file, and the agency did not provide a reason for its release.

Last year, Zia launched the Vincent Chin Institute, an advocacy organization to counter hatred against Asian Americans.

Chin’s case has had an impact beyond advocacy. Students at Harvard Law School have reenacted the trials of his attackers to highlight shortcomings in the legal system. And his killing has inspired documentaries, a podcast and a movie, “Who Killed Vincent Chin?”

Vincent Chin was a victim of brutal, racial violence, but from that tragedy emerged “a chorus of Asian American voices,” Curtis Chin says.

Considerable work ahead

The autoworkers who attacked Chin blamed foreign vehicle manufacturers for hardships in the U.S. auto industry.

This fear of foreign economic threat parallels modern “anti-China hysteria and scapegoating,” says Stop AAPI Hate co-founder Cynthia Choi, pointing to attacks on Asians by people accusing them of culpability in the COVID-19 pandemic.

“What’s different for our community today is that we are speaking out. We are speaking out loudly,” Choi says.

Established in 2020, Stop AAPI Hate advocates for policy change and collects comprehensive data on acts of hatred against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. The group has documented thousands of cases nationwide, including verbal and physical abuse, and discrimination in business and education.

“Close to 50% of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders reported that they experienced some form of race-based hate in the past year,” Choi says.

Advocates say there’s still considerable work to be done.

No comprehensive history of Asian Americans is included in core K-12 curricula. Asked to name a prominent Asian American in a recent survey, most Americans responded “I can’t think of one” or Jackie Chan, who is not American.

“We don’t even exist to most Americans,” Zia says, citing lack of visibility as a key driver in the perpetuation of Asian American stereotypes.

John Yang, the president and executive director of Asian Americans Advancing Justice — AAJC, underscores the damage of stereotypes.

“In terms of job opportunities, we are pigeonholed as perpetual foreigners,” Yang says. “Asian Americans don’t get promoted at the same rate. We don’t occupy C-suites. We don’t occupy boards in the same way that other Americans do.”

Discrimination also extends to housing. The Urban Institute, a think tank that conducts economic and policy research, reports that Asian American buyers are shown 18.8% fewer properties overall compared to white buyers. Yet the stereotype of Asian Americans as the model minority leads some fair housing advocates to exclude Asian Americans from their efforts.

“Everyone is concerned about whether an Asian American is truly an American, and so they’re not being shown the same houses,” Yang says. “They’re not being afforded the same opportunities.”

Standing on the shoulders of giants

On Sunday, dozens of residents stood with their heads bowed beneath Boston’s Chinatown gate to remember Chin. Wearing T-shirts reading “STOP ASIAN HATE,” they arranged candles in the shape of a heart and displayed a portrait of Chin with his name written in Chinese and “May 18, 1955 — June 23, 1982.”

Wilson Lee, co-founder of the Chinese American Citizens Alliance Boston Lodge and the Chinese American Heritage Foundation, said he and his wife have organized a vigil for Chin every June 23 for six years. Even as media attention faded, their dedication to Chin’s memory has not wavered.

“We’re in it for the long haul,” Lee says. “Because it’s the right thing to do, not because it’s the popular thing to do.”

A collection of local dignitaries joined the remembrance, as did 16 Asian American elementary and high school students whom Lee described as “stakeholders.” They held orange lilies and yellow flowers pressed to their chests.

“We need to make sure that future generations, especially our young people, know about the experience that he went through,” Lee says. “They are standing on the shoulders of giants, and Vincent Chin was a giant.”